Anterior Cruciate Ligament injuries are one of the most commonly repaired ligaments in the body with an estimated 100-200,000 reconstructions performed each year in the United States. Having surgery does not guarantee a return to prior level of function and those who have suffered an ACL injury, unfortunately also become higher risk for a second injury with 30% of those individuals suffering a contralateral (opposite knee) ACL injury in the first few years post-reconstruction (Grindem et al., 2016, Paterno et al, 2014) or further, elite athletes can have as high as 50% risk of reinjury in the first postoperative year (Kaeding et al, 2017). Understanding the potential contributors to re-injury risk is vital to the rehabilitation process as our goal is to get the individual or athlete back to doing what they love AND mitigating modifiable risk factors for re-injury. Non-modifiable risk factors include:

-

History of previous injury

-

Gender

-

Or age: for example being younger than 25 years old may increase risk of re-injury up to 23% as found by Wiggins et al. (2016).

While we cannot change non-modifiable risk factors, we must do our best to address the modifiable contributions to an athlete suffering a second injury and Return to Sport testing (RTS) has become an area of research emphasis recently. This is not meant to address all of the known risk factors but instead to add more depth to the Return to Sport conversation for clinicians specifically.

An important note before discussing RTS testing, there is no gold standard in place, and while we have many promising studies, there are still limitations in study design, populations, etc. and the research must be interpreted both individually, and as a cumulative body of knowledge. For example, we often reference the Kyritsis et al. study, which found a 4x higher rate of reinjury for those athletes that did not clear RTS criteria, however the sensitivity (the ability of a test to correctly identify those with the ailment) and specificity (the ability of the test to correctly identify those without the ailment) was only 54% and 79% respectively (2016). Jump testing has been a foundation assessment in RTS testing however this also is not without its criticism as Agel et al. report “this 90% rule is highly questionable because performance tests may be neither demanding nor sensitive enough to accurately identify differences between the injured and non-injured sides” (2016).

While there are limitations to the current research body, the trends continue to emerge that we need an objective criterion-based assessment to facilitate our decision making process with clearing an athlete to return to play beyond time (32% of medical providers used time ONLY as their criteria and only 13% used an objective criteria-based assessment as described by Barber-Westin and Noyes, 2011).

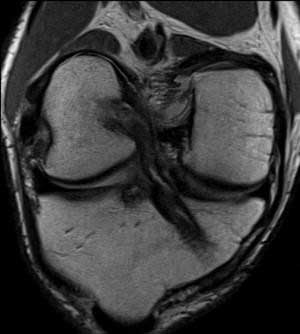

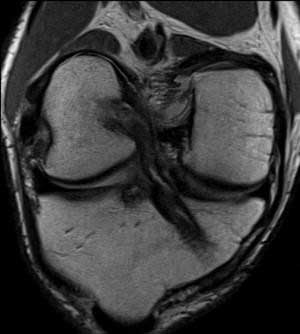

One of the most debated areas in RTS testing is WHEN can the athlete safely return to play? It has been established routinely in the literature that the risk of re-injury is highest in the 6-12 months post-reconstruction (Grindem et al., 2016, Kyritsis et al., 2016, Schlumberger et al., 2015). Grindem et al. additionally demonstrated that for every month after 6 months post-op that we delay an athlete’s return to play, the risk of reinjury decreases by 50% up until 9 months (84% total risk reduction) with no significant decrease noted beyond the nine-month mark. Similar to the previously mentioned RTS questions on validity, Capin et al. (2016) demonstrated that of the 14 athletes who cleared RTS testing, the 7 that met their RTS criteria more quickly (6.8 +/- 1.9 months) suffered second ACL injuries compared to those that met their RTS criteria later (9.5 +/1 1.9 months) and did not suffer a second ACL injury. Although a small sample pool, it is compelling information that RTS criteria cannot be used in isolation for clinical decision making in clearing an athlete to return to play. Another important consideration is the athlete’s age at the time of reconstruction. Webster et al. published a single-surgeon study showing a 6x higher rate of ipsilateral ACL injury in athletes under 20 years of age compared to controls (2014) with Magnussed et al. showing a 14.3% reinjury rate in the same age group (compared to 0.7% in those over 20 years of age) and further elaborate that 11 of the 18 reinjuries were in competitive athletes. Additionally, while MRI findings are not well correlated to outcomes when assessing sport readiness, Rabuck et al. (2016) has shown marked MRI signal changes between the 6 and 10-month mark for ACL revascularization.

6 months vs 10 months, (image source: Rabuck et al., 2016)

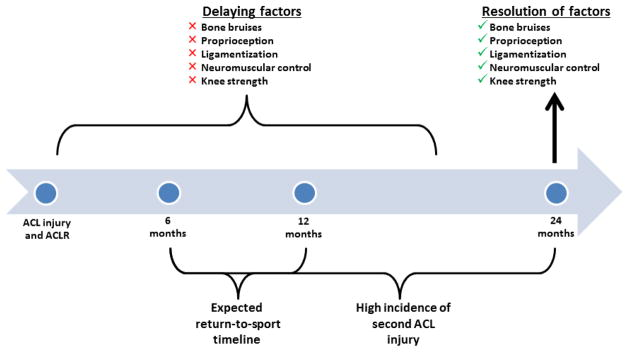

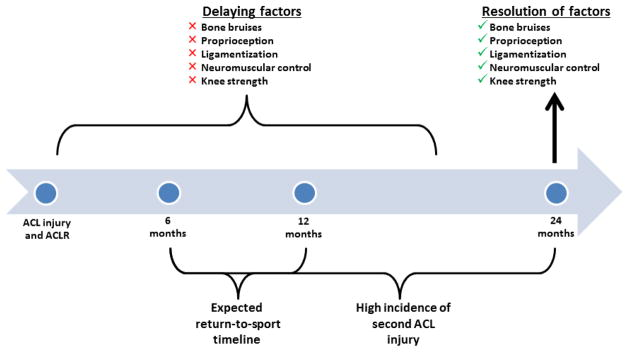

Additionally, Nagelli and Hewett (2017) recently published an article stating that athletes “require a longer postoperative recovery period than the typically advocated 6 to 12 months to facilitate the biological recovery of the joint” with specific attention to bone-bruising which “may be recovering up to one year following ACLR and require a longer recovery period than the standard timeline according to which athletes are returning to activity”. Similar to the Rabuck study mentioned above, in regard to ACL revascularization, the researchers cite a study performed by Zaffagnini et al. that demonstrated the ACL is continuing to remodel up until 24 months after reconstruction and hamstring grafts showing a delayed remodeling phase occurring between 12-24 months in comparison to the 6-12 month timeline seen in patellar tendon autografts (Pauzenberger et al., 2013). While it is unlikely that this 24-month timeline argued for by Nagelli and Hewett will be adopted in NCAA and professional athletics until additional research is done on reinjury rates on those delayed to RTS to 24 months, it does highlight that many of the early return to sport decision making criteria may not be in the best interests of the athlete and that healing (and subsequent reduction of reinjury) may be much longer than current industry standards and expectations.

image source: Nagelli and Hewett, 2017

In conclusion, while there is no consensus on what the criteria should be for Return to Sport testing, the trend in the evidence suggests we need to consider many things to maximize our reduction in an athlete’s reinjury risk. At Nevada Physical Therapy, we use 10-point criteria-based test to address multiple areas including subjective readiness, hamstring and quadriceps strength, functional performance such as hop testing, single leg squat, etc. and more. For a full breakdown on our RTS criteria, please see our protocol here. Based off the current best evidence, we believe an athlete should wait until at least 9 months, depending on their age and sport, before being cleared once they have passed all objective testing. While the trend in athletics has been an accelerated 6-month protocol, the current evidence does not support this approach and setting appropriate expectations early in the rehab process is essential. If you have any questions or concerns regarding this post, please do not hesitate to reach out.

References:

-

Agel, J, Rockwood, T, Klossner, D. Collegiate ACL injury rates across 15 sports: national collegiate athletic association injury surveillance system data update (2004-2005 through 2012-2013). Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26:518-523

-

Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, et al. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(21):1543–52.

-

Barber-Westin SD, Noyes FR. Factors used to determine return to unrestricted sports activities after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(12):1697–705.

-

Capin JJ, Khandha A, Zarzycki R, et al. Gait mechanics and second ACL rupture: implications for delaying return-to-sport. J Orthop Res. 2016;35(9): 1894–1901

-

Daruwalla JH, Greis PE, Hancock R, ASP Collaborative Group, Xerogeanes JW. Rates and determinants of return to play after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in NCAA Division 1 college football athletes: a study of the ACC, SEC, and PAC-12 conferences. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(8):2325967114543901

-

Dingenen, B. & Gokeler, Optimization of the Return-to-Sport Paradigm After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Critical Step Back to Move Forward A. Sports Med (2017) 47: 1487

-

Grindem, H, Snyder-Mackler, L, Moksnes, H, Engebretsen, L, Risberg, MA. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:804-808

-

Hildebrandt, C, Müller, L, Zisch, B, Huber, R, Fink, C, Raschner, C. Functional assessments for decision-making regarding return to sports following ACL reconstruction. Part I: development of a new test battery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:1273-1281

-

Kaeding, CC, Léger-St-Jean, B, Magnussen, RA. Epidemiology and diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Clin Sports Med. 2017;36:1-8.

-

Kaplan, Y., & Witvrouw, E. (2019). When Is It Safe to Return to Sport After ACL Reconstruction? Reviewing the Criteria. Sports Health, 11(4), 301–305.

-

Kyritsis P, Bahr R, Landreau P, et al. Likelihood of ACL graft rupture: not meeting six clinical discharge criteria before return to sport is associated with a four times greater risk of rupture. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(15):946–51

-

Magnussen RA, Lawrence JT, West RL, Toth AP, Taylor DC, Garrett WE. Graft size and patient age are predictors of early revision after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring autograft. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):526–531.

-

Nagelli CV, Hewett TE. Should return to sport be delayed until 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? Biological and functional considerations. Sports Med. 2017;47(2):221–232.

-

Paterno MV, Rauh MJ, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Incidence of second ACL injuries 2 years after primary ACL reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1567–1573

-

Pauzenberger L, Syre S, Schurz M. “Ligamentization” in hamstring tendon grafts after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review of the literature and a glimpse into the future. Arthroscopy. 2013 Oct;29(10):1712–21

-

Schlumberger M, Schuster P, Schulz M, et al. Traumatic graft rupture after primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: retrospective analysis of incidence and risk factors in 2915 cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015.

-

Walden M, Hagglund M, Magnusson H, et al. ACL injuries in men’s professional football: a 15-year prospective study on time trends and return-to-play rates reveals only 65% of players still play at the top level 3 years after ACL rupture. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(12):744–50.

-

Webster KE, Feller JA, Leigh WB, Richmond AK. Younger patients are at increased risk for graft rupture and contralateral injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(3):641–647

-

Wiggins AJ, Grandhi RK, Schneider DK, et al. Risk of secondary injury in younger athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(7):1861–76.

-

Zaffagnini S, De Pasquale V, Marchesini Reggiani L, et al. Neoligamentization process of BTPB used for ACL graft: histological evaluation from 6 months to 10 years. Knee. 2007 Mar;14(2):87–93